Mia Hughes and the Logic of Unfalsifiable Certainty

Hughes accuses gender-affirming medicine of operating on ideology while being blinded to the scandal. She is describing her own epistemic position. She has already committed to the conclusion before examining the data.

Three Claims, One Problem

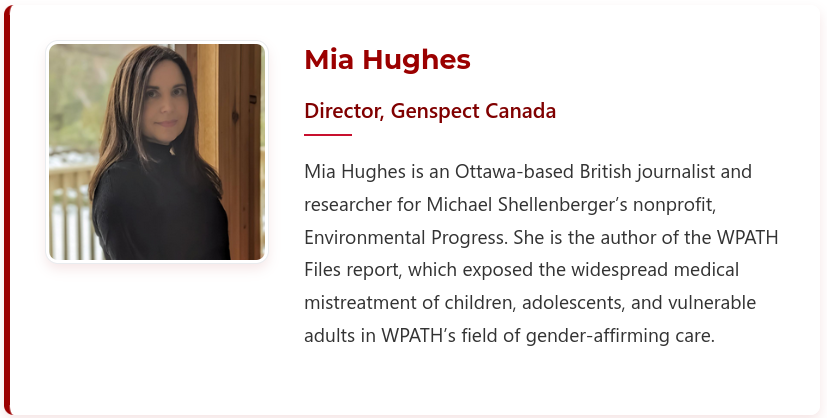

Who Is Mia Hughes and Why Her Words Matter

Mia Hughes works as director of Genspect Canada and has partnered with Michael Shellenberger's Environmental Progress organization to produce investigative content about pediatric gender medicine.[1] Over the past several years, she has become a prominent English-language voice articulating what she calls the "scandal" of gender-affirming care - a framework that treats pediatric gender medicine as a comprehensive systemic failure rather than a complex clinical landscape with genuine debates about appropriate intervention thresholds.

She speaks to policymakers. Legislators cite her 'research'. Her talks are the kind that get shared certain parents' groups and conservative media spaces, which matters because she presents herself as a reasonable analyst armed with fundamental truths rather than as an ideologue and political opponent. This presentation, reasonable, methodical, anchored in "three fundamental truths," is precisely what makes her claims worth examining carefully. People listen to Hughes because she sounds like she is thinking clearly.

She is not.

Fundamental Truth Number One: There Absolutely Are Gender-Incongruent Children

Hughes's opening claim rests on a logical impossibility: that children lack the cognitive capacity to have a stable gender identity because they also cannot distinguish appearance from reality (a developmental ability that typically emerges between ages 6 and 8).

This argument collapses under even moderate scrutiny from developmental psychology.

Children express gender identity consistently as early as ages two and three. Not as confusion, not as play-acting, but as stable self-recognition.[2] A child who says "I am a boy" or "I am a girl" at age three is expressing something cognitively present, even if the child cannot yet articulate why that identity feels true. The research distinguishes between identity (the internal sense of gender) and gender constancy (the cognitive understanding that gender is stable across situations and transformations). These are separate developments.[3]A child can have an identity before achieving constancy - much the same way a child can experience fear of the dark before understanding the physics of light.

More critically for Hughes's argument: approximately twenty to thirty percent of children express gender identity incongruent with their assigned sex before appearance-reality confusion even reaches its peak at ages four and five.[2] If appearance-reality confusion caused gender identity, these early-emerging children should not have identities at all. Yet they do, and their identities follow identical patterns of persistence and consolidation as children who express identity later.[4]

Hughes would likely respond that these early identities are not "real" gender identities but merely gender-stereotypical play. This response does something important: it redefines the evidence rather than engaging with it. When a three-year-old assigned male at birth insists consistently that they are a girl, across contexts, without parental encouragement, persisting across years, the claim that this is "just liking dolls" becomes circular. You are not disproving their identity; you are stipulating that identity does not exist, then citing the non-existence you stipulated as evidence.

The research shows something more precise: children express gender-incongruent preferences and identity, and these are not reducible to each other.[5] A child who prefers trucks to dolls may or may not have a non-modal gender identity. A child who insists they are a different gender than assigned sex shows identity expression that persists when environmental reinforcement for stereotypes is removed or even reversed.

Hughes has forgotten or chosen to ignore that identity and presentation are distinct phenomena. A child can be gender-nonconforming (rejecting stereotypes) without being transgender, or can be transgender regardless of how closely they conform to stereotypes. Her conflation of these categories, treating all gender-nonconformity as evidence that "transgender children do not exist," is not developmental psychology; it is categorical erasure dressed up as clarity.

Fundamental Truth Number Two: Adolescents Can Consent (with Proper Frameworks)

Hughes's second claim is more sophisticated and therefore more slippery: that no adolescent has the cognitive capacity to consent to interventions that carry lifetime consequences, particularly regarding fertility.

The research here is more genuinely contested than Hughes acknowledges. Recent systematic reviews of adolescent decision-making capacity in the context of gender-affirming care show that many adolescents can make informed decisions about their medical care when proper informed consent frameworks are implemented.[6][7] This is not a blanket endorsement of all interventions for all adolescents; it is a more granular finding: adolescents differ in decision making capacity, and capacity is not a binary state but a spectrum that develops across the teenage years.[8]

Where Hughes is partially correct: adolescents do show predictable cognitive limitations around forecasting long-term consequences, particularly regarding experiences they have not yet had. Her personal anecdote about shifting from not wanting children at fourteen to wanting them at thirty is real data about adolescent development - but it is not universal data. Some adolescents do change their minds about parenthood; others do not. The research on gender identity shows greater than eighty percent persistence in youth who identify as transgender in late adolescence, suggesting more stability than Hughes's own life trajectory demonstrates.[4]

The consent question also assumes a false premise: that the only alternative to "all interventions for all adolescents" is "no interventions for any adolescents." Actual clinical practice operates in the middle. Puberty blockers, the most reversible intervention, allow time for decision-making without forcing irreversible changes during a period of maximal biological flux. Hormone therapy involves informed consent processes with documented discussion of fertility, sexual function, and long-term health implications.[9] Surgery is appropriately restricted to older adolescents or adults in most jurisdictions (18+).

What Hughes dismisses as insufficient precaution is actually standard-of-care risk management: proportioning intervention reversibility to developmental stage.[10] A reversible intervention appropriate for a thirteen-year-old to consent to is not the same as an irreversible one. Hughes flattens this distinction and then uses the flattening as evidence that no consent is possible.

Her cited anecdote from a pediatric endocrinologist, that discussing fertility preservation with a fourteen-year-old is "like talking to a blank wall," is presented as general developmental law. It may reflect one clinician's experience or communication style. It does not reflect the capacity of all fourteen-year-olds to understand information about fertility when that information is presented in a developmentally appropriate manner.[2] Adolescents can grasp "this medicine might affect whether you can have biological children later" even if they struggle with the emotional weight of that knowledge. Understanding and caring deeply about something are not the same as lacking capacity to understand.

Fundamental Truth Number Three: The Social Contagion Claim Fails the Simplest Test

This is where Hughes's argument encounters data it cannot explain away.

She argues that trans identification spread through social contagion starting in 2014, that the visibility of trans people (Laverne Cox on Time magazine's cover, trans characters in media, social media amplification) caused previously non-transgender adolescents to "catch" transgender identity the way adolescent girls in Germany spontaneously developed Tourette's-like tics after exposure to a TikTok creator with Tourette's.

The argument is intuitive. The data, however, does not support it.

If social contagion drove the increase in trans-identified youth, we would expect the increase to be roughly equally distributed across sex assigned at birth. Contagion spreads through peer networks and media exposure, which should affect adolescents assigned female at birth (AFAB) and those assigned male at birth (AMAB) at similar rates.

They do not.

Adolescents assigned female at birth have begun transitioning and coming out at younger ages than adolescents assigned male at birth, roughly a two-year difference on average.[11] This pattern persists across multiple datasets and countries with different media environments.[12]

Why would social contagion produce a sex-based difference? Hughes does not explain this. Her framework assumes uniform exposure (all adolescents see the same media) and therefore should predict similar uptake across sexes.

The data instead aligns with a developmental fact she does not address: girls enter puberty approximately two years earlier than boys. AFAB puberty onset occurs at ages 10–13 (mean); AMAB puberty onset occurs at ages 12–16 (mean).[13] If gender dysphoria re-emerges or intensifies when biological development creates irreconcilable incongruence between internal identity and body, we would predict earlier emergence in those experiencing earlier puberty.

That is exactly what the data shows.

Trans men (AFAB) come out earlier not because media made girls more susceptible to contagion, but because they encountered the biological trigger, pubertal changes directly incongruent with internal identity, earlier.[14] The mechanism Hughes proposes (social contagion) predicts the wrong pattern. The mechanism actually supported by the data (identity suppression followed by puberty-driven re-emergence) predicts the observed pattern precisely.

This matters because it is not vague. Hughes is not saying "social contagion might play some role." She is claiming it explains the observed increase. She is wrong. The sex-based difference in coming-out age is a fact her theory cannot accommodate.

There is a separate finding worth highlighting: adolescents assigned female at birth are not more likely than those assigned male at birth to identify as transgender.[15] This directly contradicts the contagion hypothesis, which posits that girls have been disproportionately "infected" by the trend. They have not. What has changed is not the proportion of trans-identified youth relative to sex assigned at birth, but the age at which youth seek care—earlier for AFAB youth, corresponding to their earlier puberty.

Hughes's response to this evidence, based on her speaking patterns, is typically to cite parent-reported surveys (often from websites like ParentsofROGDKids.com) rather than epidemiological data.[16] Parent reports of sudden onset are important clinical information. They do not, however, prove contagion. A parent may perceive identity as sudden because the child suppressed it until a threshold moment (puberty, safety, peer support) made suppression unsustainable. The parent's perception of suddenness reflects when the child revealed identity, not when identity emerged. We can more accurately define the underlying phenomenon reported as "Rapid Onset Parental Discovery."

The Architecture of Certainty Without Evidence

What connects Hughes's three claims is not data; it is a rhetorical structure that makes falsification impossible.

When developmental research shows children have stable gender identities before appearance-reality confusion peaks, Hughes redefines what counts as a "real" identity. When informed consent frameworks demonstrate that many adolescents can consent, Hughes shifts to an absolutist position: no adolescent can consent to any intervention with lifetime effects. When sex-based differences in coming-out age contradict social contagion theory, Hughes cites parental perception rather than engaging with the demographic data.

Each move is a retreat to unfalsifiability. And unfalsifiable claims are not scientific claims; they are ideological commitments. They are positions held not because evidence supports them, but because no evidence could possibly overturn them.

This is what happens when you begin with "three fundamental truths" rather than with questions. Fundamental truths are not something you discover through investigation; they are something you defend against investigation. You notice only the evidence that fits. You redefine categories when evidence does not fit. You speak with the confidence of someone who has already decided what reality must be, and you interpret everything through that lens.

The irony is sharp: Hughes accuses gender-affirming medicine of operating on ideology while being blinded to the scandal. She is describing her own epistemic position. She has forgotten or ignored the developmental research. She is choosing to ignore the sex-based differences in coming-out age and other inconvenient facts. She cannot see the pattern because she has already committed to the conclusion before examining the data.

That is not clarity. That is certainty without sight.

References

[1] Genspect Canada. (n.d.). Genspect Canada. https://genspect.org/international/genspect-canada/

[2] Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Medico, D., Suerich-Gulick, F., & Temple Newhook, J. (2020). "I knew that I wasn't cis, I knew that, but I didn't know exactly": Gender identity development, expression and affirmation in youth who access gender affirming medical care. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1756551

[3] Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. N. (2010). Patterns of gender development. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100511

[4] Steensma, T. D., McGuire, J. K., Kreukels, B. P., Beekman, A. J., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2013). Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: A quantitative follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(6), 582–590.

[5] Ehrensaft, D. (2016). The gender creative child: Pathways for nurturing and supporting children who live outside gender boxes. The Experiment.

[6] Turban, J. L., Zaliznyak, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2024). Capacity to consent: A scoping review of youth decision-making in gender-affirming medical care. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(24)00178-6

[7] Cui, D., Sun, H., Olson-Kennedy, J., & Spack, N. P. (2024). Adolescent neurocognitive development and decision-making abilities in the context of gender-affirming care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 75(4), 555–561.

[8] Hidalgo, M. A., Chen, D., Garofalo, R., & Forbes, C. (2017). Ethical issues in gender-affirming care for youth. Pediatrics, 142(4), e20173088. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3088

[9] Turban, J. L., Thornton, J., & Ehrensaft, D. (2025). Biopsychosocial assessments for pubertal suppression to treat adolescent gender dysphoria. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 64(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2024.03.016

[10] See 8 above.

[11] Leinung, M. C., & Joseph, J. (2020). Changing demographics in transgender individuals seeking hormonal therapy: Are trans women more common than trans men? Transgender Health, 5(4), 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0070

[12] Ibid.

[13] Sun, C. F., Xie, H., Metsutnan, V., Draeger, J. H., Lin, Y., Hankey, M. S., & Kablinger, A. S. (2023). The mean age of gender dysphoria diagnosis is decreasing. General Psychiatry, 36(3), e100972. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2022-100972

[14] See 6 above.

[15] Turban, J. L., Flores, A. R., & Austin, S. B. (2022). Sex assigned at birth ratio among transgender and gender nonconforming adolescents in Canada. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(7), 645–647. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0795

[16] Littman, L. (2018). Parent reports of adolescents and young adults perceived to show signs of a rapid onset of gender dysphoria. PLOS ONE, 13(8), e0202330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202330